KELLI CASEMAN

Does journalism have a fourth wall?

The fourth wall is a concept usually reserved for film, theater, and fiction — a convention that imagines a wall between actors and their audience. Performers act as if we, the audience, are not there. They leave the viewer to become a kind of voyeur, observing the story.

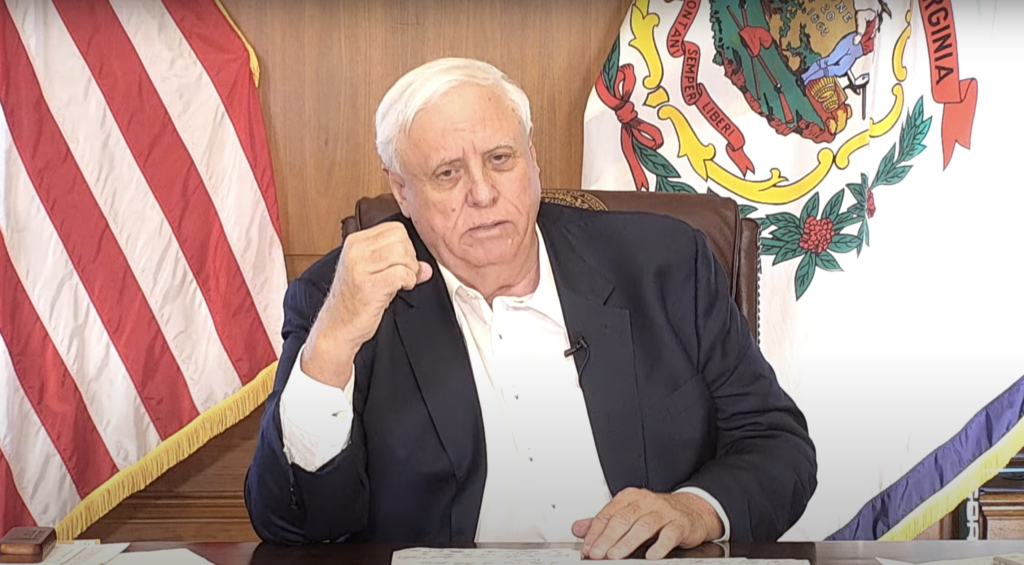

For several years, we’ve watched Gov. Jim Justice’s administration craft specific strategies to communicate with the media and control the public narrative. It’s become highly choreographed, with specific boundaries in place to control the flow of information.

For example, since the onset of the pandemic, Gov. Justice has held what he calls “media briefings” or “administrative update briefings” where reporters aren’t even in the same room. It’s all his stage. Journalists are merely expendable players. If they ask the wrong question, they won’t be invited back.

We watched in late 2022 as investigative reporter Amelia Ferrell Knisely was unceremoniously fired from West Virginia Public Broadcasting in apparent retaliation for her dogged reporting on our state’s child welfare system. And we watched during the last legislative session when the legislature passed Senate Bill 844, a bill that strips away our state’s public media from editorial independence and places the authority to hire West Virginia Public Broadcasting’s executive director in the hands of the administration’s cabinet secretary for the Department of Arts, Culture, and History.

We’ve watched state public information officers for government offices stop sharing public information. Government employees stopped returning reporter’s calls for comment. Our state systems have stopped honoring Freedom of Information Act (FOIA) requests. FOIA allows the public to request access to records from any federal agency. West Virginia Code §29B-1-1 requires government entities to provide “full and complete” information when requested unless the information falls under specific, relatively narrow exemptions. The code reads, in part:

“The people, in delegating authority, do not give their public servants the right to decide what is good for the people to know and what is not good for them to know.”

Public records are just that. And yet, here we are.

In March, an elderly man in the state’s custody died after being burned alive in a whirlpool with water at 134 degrees. For context, hot tub water is usually around 100-102 degrees. Del. Amy Summers, chairwoman of the House Health Committee, submitted an op-ed to state media, saying that a legislative oversight meeting with the Department of Health Facilities secretary had been canceled without notice. The secretary didn’t even bother to respond to her requests to explain why they did it.

That’s right: An elected official took to the media to articulate her frustration with continued stonewalling from our government because she couldn’t get answers from them in her role as chair of the House Health Committee.

And then there’s the terrible story of Kyneddi Miller, the 14-year-old girl whose emaciated body was found on a foam pad in the family’s bathroom. Days after the story became public, during his daily streaming show, the governor said that CPS knew nothing. He walked that back days later.

Last Friday, the secretary of the West Virginia Department of Human Services told a reporter that CPS had never been referred to the family — didn’t even have a piece of paper with this child’s name on it in their system.

Except on that same day, the state police responded to a FOIA request showing that they had referred the family to CPS over a year ago.

That was almost a week ago since that FOIA request uncovered what looks like a blatant lie, and we haven’t heard a word from the governor or CPS since.

Are you angry yet?

Even if you hate the media, you know that government transparency is a good thing. They work for us! And yet, our state government is acting as if they have no obligation to the public. It’s all a show, and they’re hoping no one is watching.

That’s why we really have to hand it to our local media. Instead of shying away from reporting on stories where state systems refuse to divulge information — even when required by law to share it — they’re making the stonewalling the story.

They’ve adapted — from writing simple lines like a government official “couldn’t be reached for comment” to detailing their process of investigating stories and the obfuscation tactics employed to keep them at bay. They share graphics of wildly redacted FOIA documents. They amplify each other’s articles on social media when one of them makes headway on a story they’re all working on but not getting anywhere because government agencies won’t respond to their requests.

If a reporter is disinvited to the governor’s streaming events, another may continue the same line of questioning that got the other one removed. And they’ll talk about it on social media, so we can see what’s going on.

Local media is pulling down the fourth wall to let us, their audience, know why we don’t know what we don’t know, and it’s making a big difference. Where our government systems have built a wall, the media has pulled back the curtains. Let’s hope that letting us in on the process illuminates the problem and forces our state systems to be more transparent and accountable to the public.

https://westvirginiawatch.com/2024/05/16/in-west-virginia-the-media-cannot-be-played/ – Source

The fox is in the hen house.