A look at what happened then and legislative efforts to rollback regulations since 2014

BY: CAITY COYNE AND LORI KERSEY

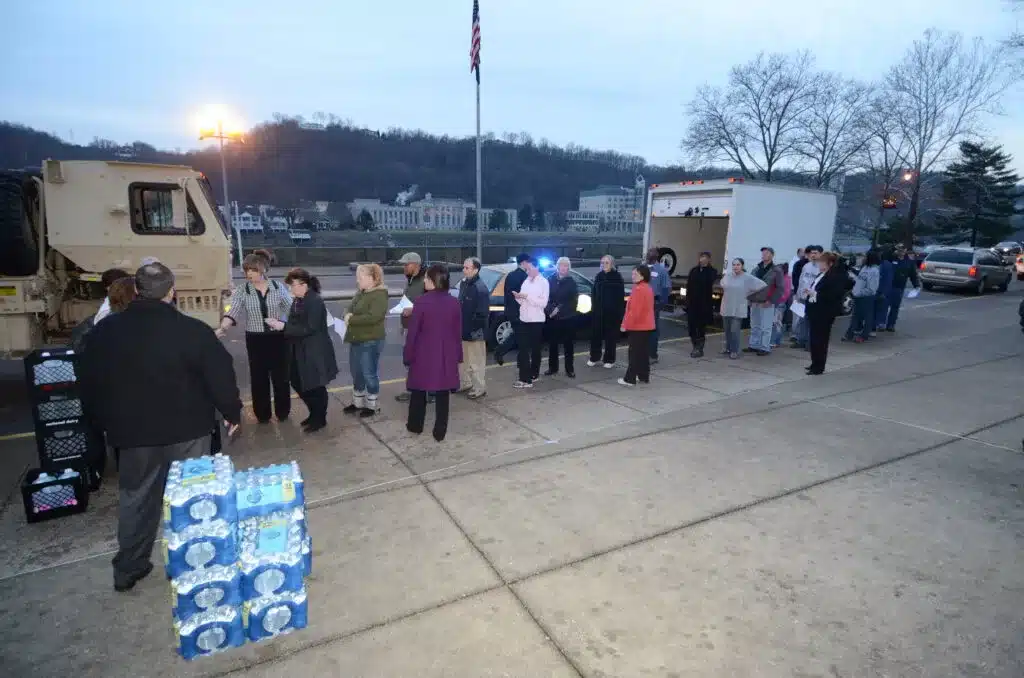

People line up outside the West Virginia State Capitol in Charleston, W.Va., after the Jan. 9, 2014 chemical spill left residents of nine West Virginia counties without consumable water for days. (Gov. Earl Ray Tomblin’s Flickr account | File photo)

Ten years have passed, but former Charleston mayor Danny Jones still recalls the winter day when a man stopped by city hall and told him something was wrong with the water. It tasted like licorice, he said.

Jones followed the man to his office down the street and tried the water himself.

“[I] took a drink of it, and I said, ‘We’re in big trouble,’” Jones said. “Because if it’s coming out of there, it’s coming out everywhere. And why would it just be here?”

On Jan. 9, 2014, a tank containing the coal-cleaning chemical MCHM leaked from Freedom Industries into the Elk River, contaminating the water supply for residents of nine West Virginia counties, mostly in the Kanawha Valley. As many as 300,000 residents were ordered not to drink or bathe in the tap water for days.

Kanawha County Commission President Kent Carper was in the middle of a commission meeting that afternoon, listening to a resident complain about his cell phone service when he got a phone call that a county staff member suggested he take.

“I said, ‘I really can’t do that right now. We’re in the middle of a commission meeting,’” Carper said. “They said, ‘Well, it’s the governor.’”

The meeting was put on hold while Carper took the call from then-Gov. Earl Ray Tomblin.

“He said it was very bad, and the advice he was getting was that all the water had to be shut down. They had to shut the water off, they didnt know for how long. At that time they were even talking about how you couldn’t use a toilet.”

Carper recalls getting off the phone and calling Dr. Rahul Gupta, who was then the health officer for the Kanawha-Charleston Health Department. Gupta, now drug czar for the United States, was in Washington D.C. at the time. Carper encouraged him to get back to Charleston as quickly as possible.

“After that it was nonstop for a couple of months,” Carper said.

Carper puts the water crisis “in the top” of emergencies he’s experienced over his career in county government. The county used armed deputies to guard tractor trailer loads of water that they’d brought in to distribute.

“I don’t want to say it was an apocalyptic type thing, but people were panicking,” Carper said.

“People were going to the local big box stores and just stealing water and buying it until there was none left. I mean, people, understandably, were panicking.”

C.W. Sigman, then the deputy director and now the director of emergency management for Kanawha County, said in his career responding to emergencies, the water crisis was unique in its magnitude.

Prior to that, he’d dealt with isolated water issues when a water line would break and affect one community, or a smaller utility company would have an issue that affected a town.

“But to cover not all of the county but a big part of it, and a big part of Southern West Virginia, its magnitude was probably the biggest deal,” he said.

Officials had varying opinions about what needed to be done to respond to the crisis. Not much was known about the chemical’s effect on humans.

Trucks hauling MCHM at the time were not required to have a placard warning sign because it had not been established to pose an unreasonable risk to transport, Sigman said.

“There was not much data on it being a hazard,” Sigman said. “But it had such a strong taste to it that it appeared to be a hazard. I can’t speak and tell you that it was not a hazard. But at the time, it was not listed as a hazardous material.”

Jones said West Virginia American Water made a mistake by not cutting off the water.

“They said, ‘Well we thought somebody [could have] had a fire.’ Well we would have come up with some water for a fire,” Jones said. “The fact of the matter is nobody had one. So all that stuff contaminated all the lines. And it got into the system.”

But Sigman and Carper said turning off the water for up to 300,000 Kanawha Valley residents would have caused its own set of problems.

“Think about what would have happened if they had to close that intake?” Sigman said. “We would not have fire hydrants. We would not have water in the hospitals for flushing or at homes to flush with. Hospitals couldn’t stay occupied because they wouldn’t have water for their fire sprinkler systems or any fire protection.

“If the system had gone completely dry, how long would it take the water company to re-energize that system and how much problems would they have where it’s been dry?” Sigman said.

Even after the do-not-use order was lifted, fear about the water’s safety lingered for a month, Jones said.

Flats and gallons of bottled water were being delivered to Charleston and beyond by the truckload. People lined up at the state Capitol waiting to receive an allotment for cooking, drinking and bathing. Even after the water was deemed safe for consumption, many still relied on bottles.

“That do-not-use advisory only lasted for five days, but people were not trusting for much, much longer,” said Maria Russo, the Clean Water Campaign coordinator for nonprofit environmental advocacy group the West Virginia Rivers Coalition. “They were really scared … it was absurd how long it took for the information to get to the public [when the spill happened], and once people were told it was safe, well they were still afraid and with good reason.”

Former state Gov. Earl Ray Tomlin (left) speaks during a Jan. 10, 2014 press conference about the Elk River chemical spill alongside now retired Major General James Hoyer, former Department of Health and Human Services secretary Karen Bowling and former state health officer Dr. Letitia Teirney. (Gov. Earl Ray Tomblin’s Flickr account | File photo)

Charleston Mayor Amy Shuler Goodwin was working as Tomblin’s communications director during the water crisis. She remembers that day meeting with the governor, his chief of staff, officials from the West Virginia National Guard and emergency services before going to West Virginia American Water for a better understanding of what was going on.

With any disaster, the first thing a communications director should do is offer clear, factual information, she said.

“The problem is… very much like the West Side [gas outage] that we just had here most recently is that we didn’t have a lot of factual information,” Goodwin said. “We were getting bits and pieces of information, but factual information and information that everyone felt confident about — that’s always the struggle when you’re dealing with a crisis.”

The governor’s office held a press conference and set up emergency operations, she said

“I slept at the office for two days,” she said. “I bathed in the sink. My husband came down and gave me gallons of water, and I stayed there for two days. I remember that very vividly. Those are things you don’t forget.”

In the aftermath of the chemical spill, West Virginia American Water faced criticism that it didn’t respond quickly enough once it realized there was a chemical spill. A class action lawsuit against the water company and Eastman Chemical Co. over the water crisis was ultimately settled in federal court for $151 million. For their role, Freedom Industries officials faced criminal charges for pollution crimes relating to the spill.

“West Virginia American Water believes that we responded appropriately to the information we had and worked closely with a variety of government agencies to address the circumstances created by the Freedom Industries spill,” said Megan Hannah, senior manager for Government and External Affairs at West Virginia American Water, in an emailed statement.

Since the crisis, some officials say residents of the Kanawha Valley are no better protected from the threat of chemical spills in water than they were in 2014.

“In fact, the Legislature has further deregulated inspection and management of these independent tanks all over the place,” Carper said. “They have good lobbyists.”

Some called for the water company to open a second water intake, but it never happened.

“A catastrophic event could occur on the Elk River and end up shutting down the water supply,” Carper said.

Michael Mayhorn, Boone County’s director of emergency management, echoed Carper’s sentiments. Mayhorn was working in the 911 center’s addressing office during the crisis, but was assigned to help distribute bottled water.

The water company may monitor the water more closely, and reporting requirements may be more stringent, he said, but he doesn’t believe that would make a difference.

“If something happened that nobody knew, and something got into the water, I don’t know that it wouldn’t make it through the system somehow,” Mayhorn said. “I don’t think there’s a way that we can completely mitigate that.

West Virginia American Water: “The spider”

The politics and business of water is complicated. Infrastructure projects are expensive, especially in a poor state where population loss means fewer customers available to help spread the costs for upgrades and improvements.

Small, understaffed water utilities are widespread in the state, and often as their expenses increase, the quality of service they can provide decreases. For the past several years, private company West Virginia American Water has committed to expanding its reach in the Kanawha Valley, acquiring and operating several previously struggling water systems.

In the wake of the water crisis, some residents in the Kanawha Valley started to push for a de-privatization of the region’s water system, meaning the service would revert into the hands of the people who live there.

Such efforts, however, were unsuccessful, and now American Water reaches farther than ever before. In an emailed statement, representatives for the company said its reach is a benefit for those struggling systems. With more financial resources, American Water can tackle issues smaller utilities cannot.

“From aging infrastructure to contaminants like PFAS to lead and copper and extreme weather events, communities have many different reasons for deciding to turn to a reliable water company to own and operate its systems,” said Hannah wrote in an email. “Our conversations with those communities center around what makes sense for the community and what is in the best interest of those customers. Our customers can benefit from growth as it contributes to the spreading of long-term fixed costs that can help with long-term rate stability.”

The recent expansion mirrors the company’s business strategy of the 1990s, when local leaders started referring to West Virginia American Water as “the spider” due to its reliance on pulling in and taking over other small systems for its own survival and benefit, much like a spider catching insects in its web.

These acquisitions — as well as water sales and operational agreements, where the large company agrees to sell water or take over management of struggling utilities — have sprawled through eastern Kanawha County and into the southern part of the state over the last decade.

As of 2024, there is only one public water utility — St. Albans Municipal Utility Commission — left operating in Kanawha County and just three in neighboring Fayette County.

The company’s growth, coupled with a lack of investment and legislation to better oversee potential contamination, could be a cause for concern, Russo said. But it’s also complicated; often, a takeover by the larger company means more immediately reliable service for people in the region. The question that remains, however, is what risks could potentially come with the improvements.

“A lot of our municipal systems have aging infrastructure, they don’t have the resources to distribute water the way they need to. That’s when American Water steps in, but — and in part because of the water crisis — people have very big and valid concerns against the expansion of privatized water systems, because they don’t know who to trust,” Russo said.

“I think this should really be the state’s responsibility as well,” she continued. “American Water [performing acquisitions] is one way to solve the issue for now, but maybe there are other approaches that the state could take to help but we’re not attempting.”

Members of the West Virginia National Guard distribute bottled water outside the state Capitol after the 2014 Freedom Industries chemical spill, in Charleston, W.Va. (Gov. Earl Ray Tomblin’s Flickr account | File photo)

Regulatory rollbacks and the hope for a ‘water secure’ future

Chemicals from the Freedom Industries spill seeped into the Kanawha Valley’s water lines just one day after legislators convened at the Capitol for the start of the 2014 regular session.

That year, in response to the water crisis, lawmakers passed Senate Bill 373, a landmark piece of legislation meant to increase regulation and oversight of aboveground storage tanks for chemicals, oil and gas. The law garnered bipartisan support in both chambers of the Legislature and went into effect on June 6, 2014.

SB 373 implemented a first-of-its kind regulatory program for aboveground storage tanks, requiring regular registration, certified inspections and the creation of spill prevention response plans for companies.

As with many similar prevention plans for pollution and contamination, however, the law relied on self-reporting and cooperation from chemical, oil and gas companies storing materials that could pose threats. Mechanisms for the state to enforce and oversee the self-reporting were lacking in the bill and an ongoing shortage of certified inspectors meant wiggle room for corporations that said the regulatory requirements were expensive and burdensome.

Russo, with the Rivers Coalition, said the idea of corporations self-reporting the risks they pose to the public is a concern. More recently, she’s seen pushback from industry and legislators when it comes to tracking and attempting to regulate per- and polyfluorinated substances (or PFAs, commonly referred to as forever chemicals) in the state’s water sources.

“It’s difficult because yes, we want to be able to trust that self-reporting can work, but we also need to recognize that these are really powerful industries and they have a lot of priorities to balance,” Russo said. “Unfortunately, those priorities aren’t always going to be in the best interest of the public or public health.”

A year after the chemical spill, as the licorice smell of the water that once permeated the Kanawha Valley dissipated, so too did legislative efforts to prevent a similar crisis from occurring again.

In 2015, with a freshly elected Legislature — the first in the state to be controlled by Republicans in more than 80 years — lawmakers in the new majority party, with support from several Democrats, began what is now a continuous effort to chip away at the previously passed regulations.

That year, they approved SB 423, which made exemptions to the Aboveground Storage Tank Act to require inspection only for tanks holding 50,000 gallons or more of hazardous materials or those within a “zone of critical concern.” Those zones are areas near surface water intakes where leaked or spilled contaminants are more likely to enter a drinking water system.

The bill that ended up passing was a watered down version of the one originally introduced, which would have carved out exemptions for all but 90 — or about .2% — of the state’s more than 43,700 aboveground storage tanks, according to a 2015 analysis.

In 2017 lawmakers again rolled back the initial regulations implemented in SB 373, voting for rules that only applied to storage tanks in areas of critical concern, no matter what substance or how much of it they were used to store.

“There have been so many rollbacks over the years, and it is disappointing to watch,” Russo said. “We want to do everything we can to protect the legislation that is in place and we’re hoping, at least I’ve been told, that there shouldn’t be any more.”

The standstill comes after clean water and environmental advocates took home a rare “win” in the 2021 session, Russo said. That year, they successfully defeated another bill that, if passed, would have carved out exemptions for tanks located within zones of critical concern.

While the cutouts to water protection efforts over the last decade have been spearheaded by industrial lobbyists and industry-minded Republicans, Russo said misunderstandings about the necessity for industrial protections is widespread.

“I still hear all the time at the Capitol, people say we ‘went too far’ with the original bill. That is the narrative of so many legislators, and they see these rollbacks as kind of being a little more reasonable,” Russo said. “I don’t agree with that, though. The most important thing here, certainly for our lawmakers, should be making sure our water is safe. The reality is there is a lot more we could be doing to ensure that.”

The 2014 chemical spill was a huge crisis, Russo continued, but every day across West Virginia, there are multiple water crises unfolding that impact thousands of people.

Throughout the entire state, forever chemicals infiltrate water systems without oversight, posing serious and unknown health risks to consumers. In the southern coalfields, dozens of communities are served by failing or distressed utilities lacking the resources to adequately deliver safe drinking water. At least 3% of West Virginia’s water service lines are suspected of containing lead, of which there is no safe exposure level for humans. Several communities have lived under years-long boil water advisories due to underground contamination from mining operations and more.

Goodwin said she’s glad the water crisis’s 10th anniversary is getting attention because it reminds officials of what they need to do so that something like it never happens again.

“Chemicals shouldn’t be stored that close to the water supply, period,” Goodwin said. “We know that. How did that happen? Let’s make sure it doesn’t happen again. And what do we do when that does happen? So always I think that anniversaries are times when we go back and say what went wrong, what went right? How can we do better? There’s always the three things that you should ask.”

On Tuesday evening, the Rivers Coalition will host an event to commemorate the efforts of the last 10 years while also looking toward a future where the issue of water safety and access isn’t up for debate.

“When we’re looking back today at the last ten years, we also want to look forward. That’s what we mean when we say we’re envisioning a water secure future. We want that for everyone and we want it every day,” Russo said. “This is especially important in West Virginia where we have so many water resources across the state and where still, people don’t have access to clean water.”

** West Virginia Watch is a nonprofit media source. Articles are shared under creative commons license. Please visit https://westvirginiawatch.com/ for more independent Mountain State news coverage.